Magical Book Revision Journey 2

Superman v.s Trump Book Revision, Chapter 2 Review

Special Programing Note

For the next few weeks, as I am working diligently on revising my book, the posting schedule will shift to Monday and Friday, with no posts on Wednesday until after Christmas.

Thank you.

So, back to book revision process: back to the revising, editing, and proofing process.

To see how I define each of these sub-processes inside the overall revision process itself, see my Monday post, Magical Book Revision Journey 1.

1-Page Chapter Openings

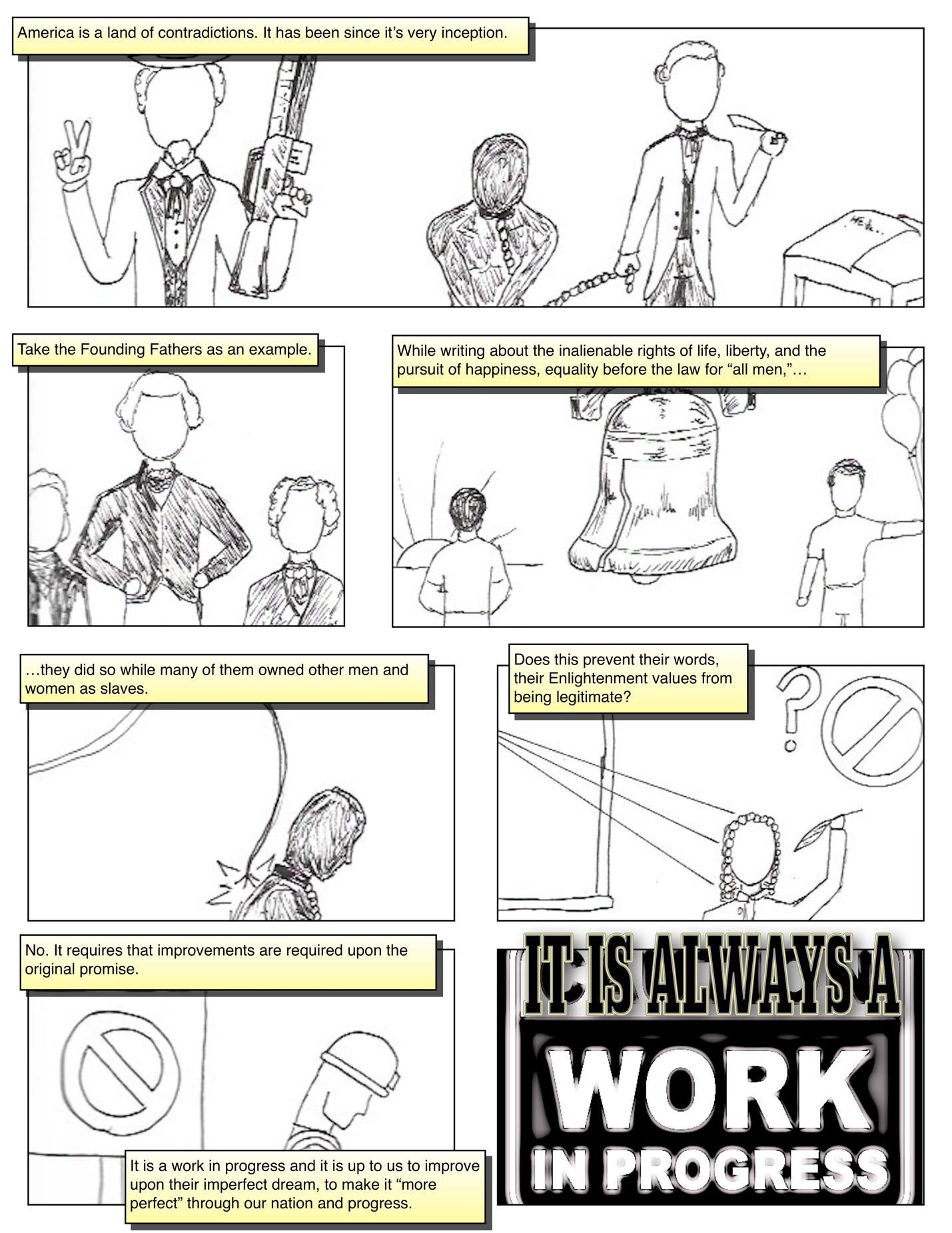

Before we jump into Chapter 2, I want to point out that I am beginning each chapter with 1-page comic book set-ups.

Chapter 1 starts with this:

Chapter 2 starts with this:

Going forward in each of this Magical Book Revision Journey, I will include these images. My plan to is to work on revising and making them look better, I did something like this with some 1-page comics from my preface that you can see in my post: Page 1, What is a Model? And Page 2, Macro and Micro of a Model. I may also enlist an artist friend to update them and make them more professional as well.

Now, on to Chapter 2…

Superman vs. Trump, Chapter 2

So, on Monday, I did a form of meta-breakdown on Chapter 1 of my book I am revising.

Chapter 2, titled Who’s Who: America opens, after a brief review of what was looked at in Chapter 1:

Who is Superman?

In the introduction to his book, Superman: An Unauthorized Biography, Glen Weldon points out that there are many possible answers for why Superman has endured in America for nearly a century. It is correct to say “answers,” plural, because Superman exists in “our planet’s collective consciousness,” and therefore each of us has formed “in our minds and hearts, our own unique idea of Superman.” Superman is an idea. He is a representation of “the values of society that produces him. That means that what, say, Superman symbolizes changes over time.” People might look at him and see simply a cis-gendered white male, but honestly, and this is my personal opinion, Superman could be anyone. Superman is anyone who lives up to the ideals and essence of Superman. He is universal, ubiquitous and iconic. One answer to Superman’s endurance lies in his ability to reflect values, American values, and to serve as a rhetorical model of them. Despite changes and evolution of decades, there always remains a core essence. Superman embodies the emulation of American excellence. He projects back to America the image of itself that is a selfless ideal America wants to believe of themselves. He embodies real American greatness while simultaneously challenging America to live up to its own self-conception every day.

I open with my first source being Glen Weldon, who I feel makes one of the most helpful statements in pointing out, and it is later quoted, the basic essence of Superman.

Here, Weldon provides us with an idea that Superman is ubiquitous with the culture he was created by. He is directly a result, as all heroes are, of the culture he emerges from. Culture and their Heroes are always interconnected.

With Danny Fingeroth, in his work Superman on the Couch, we add to the interconnected idea of Cultures and Heroes the concept that said Heroes can change, are capable of adapting and evolving.

Even with the connection to culture and ability to evolve, most heroes, at least the ones that last, have something that at their core, their essence, makes universal. Part of Superman’s core essence is that he embodies something quintessentially optimistic about American excellence.

The footnote that follows the sentence “Superman embodies the emulation of American excellence” is as follows:

American excellence is an abstract term, but for purposes found here it will be generally defined as concepts of innovation, coopetition, opportunity, hard work, honesty/integrity, and more that are usually defined by one’s personal experience in relationship to life in America.

This idea of what makes American excellence is a collection of values/ideas/virtues that are collectively accepted by most Americans. This collective set of virtues is applied and informed by the strong individuality that runs through America and American culture as well.

The Idea of…

Turning specifically to more on Superman, the continued idea of why Superman, of all the heroes that emerged before and after him, has become so universal, survived and thrived over decades as following:

Of all the superheroes populating our world today, there are two types of heroes that exist in our world. The first are those that are dated, of a time that fade away, and the second are those that continue to be relevant. These are the heroes who “resonate [by] tapping into something primal. Superman defines that archetype.” There is something deep within our cultural unconscious that allows characters, Superman being a paradigm of them, to be timeless and continue to remain relevant no matter when or where they were conceived. What keeps Superman relevant to a 21st century audience are the same as they always have been: the “allure” that comes from the desire to fly, the “love triangle” or the “secret” identity, or just perhaps the wish to “be ten years old again.” This is just one level that Superman operates on though. This is the overt, conscious level of Superman’s identification. Superman is so ubiquitous in American culture that many never stop to wonder: “Why?” What makes Superman an American superhero? The answer is that deep inside Superman exists a powerful ideal, an ideal of what America is at its very best and Superman acts as guarantor as the model of it.

We continue in this paragraph by introducing another scholar, one who was kind enough to share with me resources when I reached out to him when I was drafting my dissertation, Larry Tye. He calls Superman “an archetype.” Later in the same paragraph I record what Tye notes as common tropes in Superman stories – being able to fly, love triangle, etc.

Near the end of the paragraph I end a sentence with “Superman’s identification.” This is my first introduction of the rhetorical idea of identification as espoused by Kenneth Burke. In two works, as I elaborated on in the footnote, the Rhetoric of Motives and Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method, he discusses a great deal on how this principle operates.

In the Rhetoric of Motives, Burke notes that the function of identification occurs both before the change has occurred and afterwards, in order to understand that there has been a change at all. The audience must be able to recognize both what it (whatever was changed) was and what it has now become. To complicate the situation more, identification serves a larger purpose, when persuading others, to help unite different groups, positions, or divisions by offering them something larger to relate to and unify them. Burke specifically quips that “If men were not apart from one another, there would be no need for the rhetorician to proclaim their unity.”

In Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method, Burke elaborates more, saying that one identifies his or her “self” as an individual, but also as part of a group of friends, member of a community, citizen of a town, state, country, or even species. Burke refers to this as the hierarchy, or “move by a sense of order.”

It is from this point onward that I, of course introduce Donald Trump using the first of serval sources on Trump, such as:

Timothy L. O’Brien. Trump Nation: The Art of Being Donald Trump.

Mary Trump. To Much, Never Enough: How My Family Created The World’s Most Dangerous Man.

Michael Kranish and Marc Fisher, Trump Revealed: The Definitive Biography of the 45th President.

Olivia Waxman, “President Trump Played a Key Role in the Central Park Five Case. Here’s the Real History Behind When They See Us” from Time Magazine.

Edward Helmore, “How Trump’s political playbook evolved since he first ran for president in 2000” from The Guardian.

Adam Serwer, “Birtherism of a Nation” from The Atlantic.

Adam Serwer, The Cruelty is the Point.

Krishnadev Calamur, “A Short History of ‘America First’” from The Atlantic.

And more…

One very important source was David Neiwert’s book Alt-America: The Rise of the Radical Right in the Age of Trump, which helped me steel man my assertion of alternate universes emerging in America today. He calls the universe that admires Trump “alt-America” while I call it Universe Z as compared to Universe A where Superman is a model and champion of our better selves.

Arête

I go on to introduce arête as well. This will be defined more in Chapter 3 on Monday. However, to briefly define it some, I lay out that,

The Greek-English Lexicon, note that arête implies the “excellence of any kind,” and is defined as “moral virtue.” The exact meaning of arête is fluid and has shifted over time from its beginnings in classical Greece to the modern era. However, there has been a constant element to arête – its learned. From the ancient Greeks to the Enlightenment to the modern times there has been the standing belief that arête is something that can be taught and passed on to others.

More will be said on arête and its evolution, as I said, in Chapter 3.

But let us end on a positive note. We have only scratched the surface of this chapter, can’t fit it all in, but I want to close with a great transcript of narration Ryan Reynolds voices the documentary Secret Origins: The Story of DC Comics:

Once there was a world without comic books. Like jazz and like baseball like so much that is distinctly American, the comic book was born on the country’s margins: cheap, slight, juvenile. An orphan child that would transform over time into something vital and strong [with an] ambition . . . to entertain, to challenge, to captivate, to enlighten . . .

There is a brilliant message in here that from the margins of American society, it is from comic books that our salvation, our guide to listening to the ignored and dismissed can be learned, just like arête, and it is from the margins that American arête truly emerges.

Till next time!

Works Cited

Burke, Kenneth. Language as Symbolic Action: Essays on Life, Literature, and Method. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1966.

Burke, Kenneth. The Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1969.

Fingeroth, Danny. Superman on the Couch: What Superheroes Really Tell Us about Ourselves and Our Society. New York, NY: Bloomsbury, 2004.

Liddell, H. G., and Robert Scott, English-Greek Lexicon 9th Ed. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1996.

Tye, Larry. Superman: The High-Flying History of America’s Most Enduring Hero. New York: Random House.

Weldon, Glen. Superman: An Unauthorized Biography. Hoboken: Wiley, 2013.