Chapter 4: Rebutting Untruth 3-The Truth is that Everyone is Gray and Complicated

The Untruth of Us Versus Them: Life is a battle between good people and evil people.

Let Us Get This Out of the Way…

NO ONE is fully good or fully evil.

It can be easy to categorize people, to (hasty) generalize them but this constitute a logical fallacy.

However, since when, particularly if engaging in the pathos of emotional reasoning, are we inclined to pay attention to logical fallacies?

This part of The Coddling of the American Mind finds Greg and Jonathan looking into particular divisions found quite prominently today in our society, the tendency of individuals to gather into particular groups and tribes, what is often sometimes referred to as tribalism or sometimes partisanism.

Groups and Tribes

This section opens with a description of Henri Tajfel, a Polish psychologist who served in the French army in World War II and was a prisoner in Germany. He was also Jewish, and in his 1960s series of experiments where he sought “to understand the conditions under which people would discriminate against members of an outgroup” (57).

Through a series of experiments of putting people into arbitrary groups, it was natural for members of one group to identify with those within the group while showing a lack of empathy for those on the outside who were considered “others.”

What this revealed about humanity is

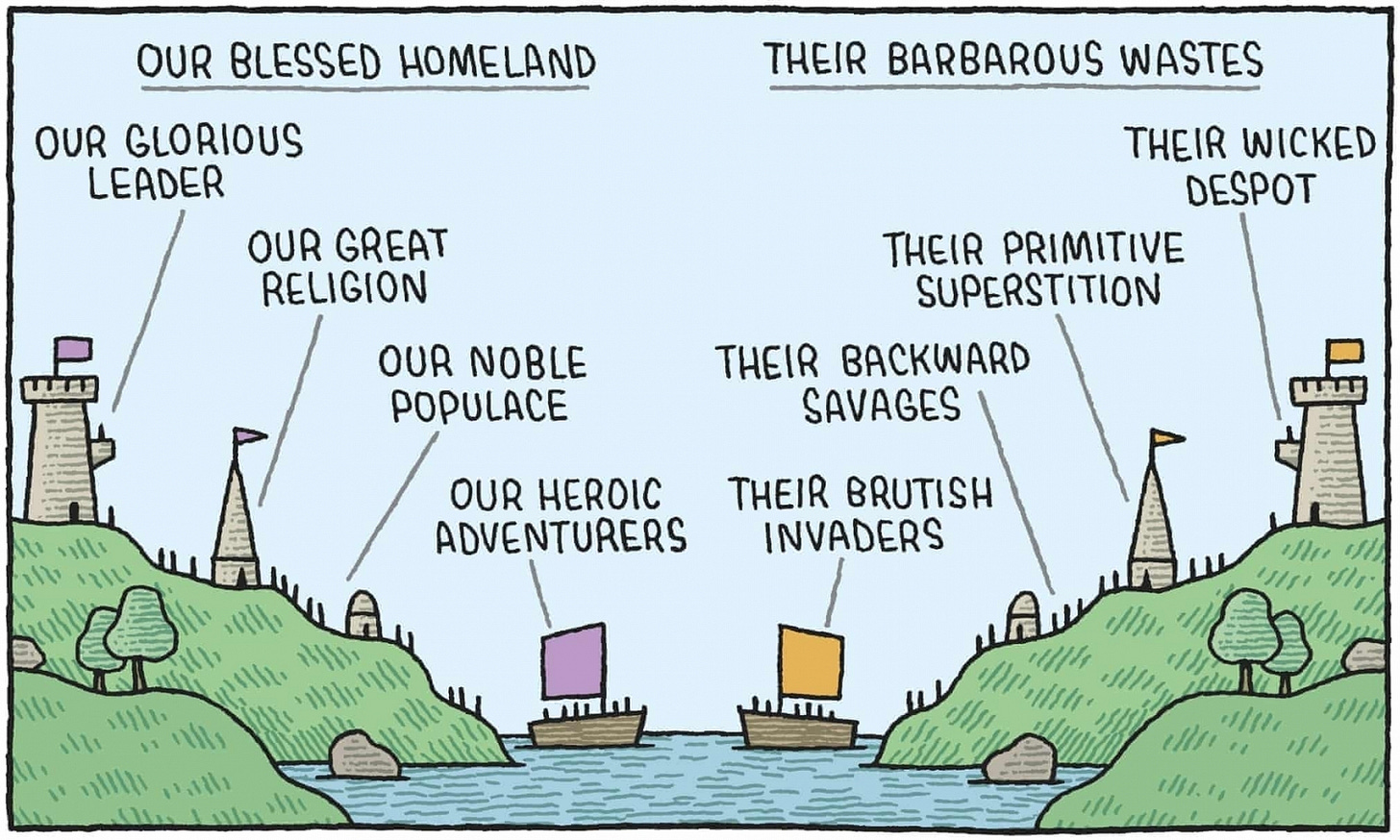

“That the human mind is prepared for tribalism. Human evolution is not just the story of individuals competing with other individuals within each group; It's also the story of groups competing with other groups–sometimes violently… Tribalism is our evolutionary endowment for banding together to prepare for intergroup conflict. When the ‘tribe switch’ [the disregard for self-interest and activation of ingroup thinking takes over] is activated, we bind ourselves more tightly to the group, we embrace and defend the group's moral matrix, and we stopped thinking for ourselves. A basic principle of moral psychology is that ‘morality binds and blinds,’ which is a useful trick for a group gearing up for a battle between ‘us’ and ‘them.’ In tribal mode, we seem to go blind to arguments and information that challenge our team's narrative. Merging with the group in this way is deeply pleasurable – as you can see from the pseudo tribal antics that accompany college football games” (58).

Now, this is a lot to take in here. Personally, I think about this rhetorically from the perspective of Kenneth Burke's notions of identification and consubstantiality.

Identification, as Brook Quigly of the University of Memphis writes, is “a process that is fundamental to being human and to communicating. He [Burke] contends that the need to identify arises out of division; Humans are born and exist as biologically separate beings and therefore seek to identify through communication, in order to overcome separateness.”

Consubstantiality is connected to Identification in that we have a desire to identify with larger ideas, groups, etc., “Yet at the same time [we] remain…, an individual locus of motives. Thus [we are] Both joined and separate, at once a distinct substance and consubstantial with another” (Burke 21).

Since I am not here to give a lesson in rhetoric at the moment, I am going to move on at this point and get back to what Greg and Jonathan were discussing.

“But being prepared for tribalism doesn't mean we have to live in tribal ways. The human mind contains many evolved cognitive ‘tools.’ We don't use all of them all the time; we draw on our toolbox as needed. Local conditions can turn the tribalism up, down, or off. Any kind of intergroup conflict (real or perceived) immediately turns tribalism up, making people highly attentive to signs that reveal which team another person is on. Traitors are punished, and fraternizing with the enemy is, too. Conditions of peace and prosperity, in contrast, generally turned down tribalism. People don't need to track group membership as vigilantly; they don't feel pressured to conform to group expectations as closely. When a community succeeds in turning down everyone's tribal circuits, there is more room for individuals to construct lives of their own choosing; there is more freedom for creative mixing of people and ideas” (59).

I don't know about anybody else but I'm reading this right now and I can't help but think of the damage, and I believe Jonathan would agree with me, social media has done to us.

Social Media is a force multiplier that has turned up the conditions of tribalism in our world today. More accurately it is the tool for which those seeking to amp up tribalism for whatever ends they devise can do so.

If you think we live in a world where everything is horrible and we are plagued by discontents, I would not be surprised because that idea is being fed to us through many different forms of media at an accelerated rate that we have never experienced before in the history of our existence.

Food for thoughts to give you nightmares.

Two Kinds of Identity Politics

Most people today have some notion of what identity politics is or at least a concept in their mind of what it is, but I think we all get it wrong.

The truth is that identity politics is quite natural, but somehow we've managed to twist it. For example, as Greg and Jonathan write, “Politics is all about groups forming the coalitions to achieve their goals. If cattle ranchers, wine enthusiasts, or libertarians banding together to promote their interests in normal politics, women, African Americans, or gay people banding together is normal politics, too” (59).

See, identity politics, not a completely dirty word. But where does it go wrong?

Greg and Jonathan have two takes on this idea, two breakdowns in how it is applied.

1. Common-Humanity Identity Politics

Martin Luther King Jr. was the archetype for this kind of politics. Racism is something that is a stain upon America and it has to be combatted, then and today. As written,

“the civil rights movement was a political movement led by African Americans and joined by others. Together, they engaged in nonviolent protests and civil disobedience, boycotts, and sophisticated public relations strategies to apply political pressure on intransigent lawmakers while working to change minds and hearts in the country at large” (62).

Greg and Jonathan use King and his approach as the epitome of the common-humanity identity politics. People learn to come together in coalitions, recognizing the unifying identification of our common bonds and identity as a whole to achieve great things.

This kind of approach politics has paved the way for many progressive successes in the 20th and 21st century. It helped bring about the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and paved the way for the marriage equality rulings by the Supreme Court as well.

“This is the way to win hearts, minds, and votes: you must appeal to the elephant (intuitive and emotional processes) as well as the rider (reasoning)… instead of shaming or demonizing…opponents…[we must humanize] them and then relentlessly appeal…to their humanity” (62).

The approach offered here is a harder one than many people realize and I also think that as a result, this is why many people give up on it. However, we really shouldn't.

2. Common-Enemy Identity Politics

Primarily, Greg and Jonathan are speaking about these kinds of identity politics is found on college campuses, but in many ways they have spread out into our culture at large.

Perhaps the largest problem is that the first one, common-humanity identity politics is being overshadowed by the second, common-enemy identity politics.

Greg and Jonathan write that the worst, absolute worst version of “common-enemy identity politics” that most people will know about is “Adolf Hitler's use of the Jews to unify and expand his Third Reich” (63).

Yikes.

There is a common trend in academics and among students today who want to see a dismantling of the old power structures that exist and they feel perpetuate inequality in order to, ideally, formulate a more equal and just system that is more inclusive.

Strangely, in that pursuit, things can go very wrong. Things can steer into another logical fallacy of either/or, like us vs. them.

Part of the push for dismantling of power structures comes from Marxist theory, based on the works of Karl Marx. Marxist theory approaches social and political analysis in terms of struggle and power. Primarily, it is “a set of approaches in which things are analyzed primarily in terms of power. Groups struggle for power. Within this paradigm, when power is perceived to be held by one group over others, there is a moral polarity: the groups seen as powerful are bad, while the groups seen as oppressed are good” (64).

Before going forward, I want to state that as a literary theory, Marxist theory is quite fascinating and useful. I can also see the sympathy for those who see it as valuable in a political and social sense as well. However, one of the things that I think Greg and Jonathan would agree with me on is that it is but one lens for seeing and viewing the world. It is not a totality. Thinking it is a totality is the problem.

Continuing on, Greg and Jonathan introduce Herbert Marcuse -

“a German philosopher and sociologist who fled the Nazis and became a professor at several American universities. His writings were influential in the 1960s and 1970s as the American left was transitioning away from its prior focus on workers versus capital to become the ‘New Left,’ which focused on civil rights, women's rights, and other social movements promoting equality and justice” (64-5).

This is where things go sideways unfortunately…as a Marxist take on equality within a struggle between powerful and powerless leads to intolerance. The goal “of a Marcusen revolution is not equality but a reversal of power” (66).

In other words, just trading places.

Speaking to proponents of fixing inequality in the words of Inigo Montoya from the Princess Bride: “You keep using that word, I do not think it means what you think it means.” Or rather, to paraphrase, “I do not think that idea means what you think it means.”

Modern Marcuseanism

This is where it all goes wrong on college campuses and spreads out into the larger culture in turn.

Greg and Jonathan point to the way we interpret ideas and theories as becoming problematic, when they note the theory of Intersectionality. Their aim is not to invalidate the theory, just as I would not seek to invalidate Marxism as all theories have uses, but sometimes good intentions breed bad outcomes.

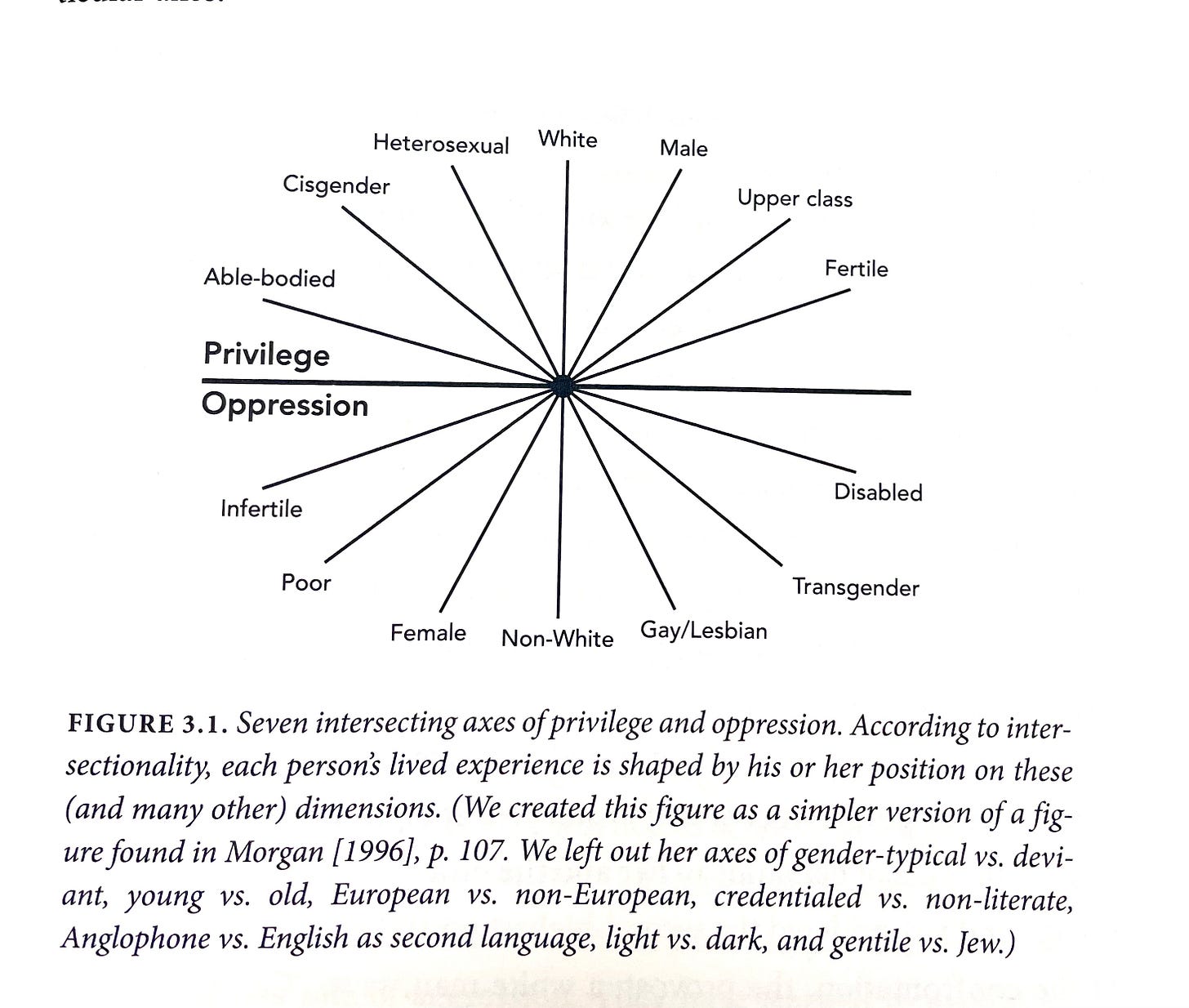

Certain interpretations of Intersectionality end up teaching “bipolar dimensions of privilege and oppression as ubiquitous in social interactions. It's not just about employment or other opportunities, it's not just about race and gender. Figure 3.1 [which I have included below] shows the sort of diagram that is sometimes used to teach intersectionality” (68).

This figure is based on one by Kathryn Morgan of the University of Toronto. She is noted as defining her terms: “privilege involves the power to dominate in systematic ways… oppression involves the lived, systematic experience of being dominated by virtue of one's position on various particular axes” (68-9).

In general, Greg and Jonathan do not disagree with Morgan on the idea of white male privilege or that certain groups have systemic advantages. Where this good idea becomes problematic is when it becomes the unitary way of thinking among individuals and groups.

This is where the Us versus Them mentality takes hold. If everything boils down to privilege versus oppression of power and domination, then anyone at the top is automatically labeled as bad and those who are underneath or not in power are good.

This is fundamentally not true.

In fact, this builds a kind of cognitive distortion in a student or person, a cognitive schemas of “Life is a battle between good people and evil people” (70). This of course plays right into the hands of tribalism.

For me, it is a lose-lose proposition.

Common-Enemy Identity Politics is Bad for Students and Common-Humanity is Needed

There is a real enemy lurking beneath all that we've been discussed here. It is the enemy of good intentions gone horribly wrong. It is not unfixable, but to fix it, it must be acknowledged first.

Greg and Jonathan point out that students learn from teachers and others, and if we fail to help them overcome misconceptions, we are perpetuating an exponentially growing problem. As they write:

“the combination of common-enemy identity politics and microaggression training creates an environment highly conducive to the development of “call-out culture,” in which students gain prestige for identifying small offense committed by members of their community, and then publicly “call-out” the offenders. One gets no points, no credit, for speaking privately and gently with an offender–in fact, that could be interpreted as colluding with the enemy. Call-out culture requires an easy way to reach an audience that can award status to people who shame or punish alleged offenders. This is one reason social media has been so transformative: there is always an audience eager to watch people being shamed, particularly when it is so easy for spectators to join in and pile on.” (72-3).

As I said earlier, force multiplier – social media.

For me this kind of thinking is completely backwards. It is the antithesis of what we should be looking for and striving to teach young people.

Worst of all, it is actually counterproductive needs and desires young people feel for a more just and equitable world. They just don't know it yet, and we haven't been wise enough to tell them.

We need to find out way to reinvigorate a common-humanity identity politics. There is a need in our country to remind ourselves that we are less divided and more united than we believe true.

Social media, interest groups, political groups and people, and more are actively are working to divide us and isolate us. Why? To service their own political ambitions.

If you worry about power and its misuse and inequality in the world today, then you really need to be building coalitions and avoiding the trap of Us versus Them.

Three Great Untruths down…on to the last and newest one!

Word Count: 2,369. With Chapters 1, 2, and 3 we are now at a grand total of 8,149 word!

Works Cited:

Burke, Kenneth. The Rhetoric of Motives. Berkeley: U of California P, 1969

Lukianoff, Greg and Jonathan Haidt. The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas are Setting Up a Generation for Failure. NY: Penguin Press, 2018.